China’s economy continues to contend with the ramifications of a housing market meltdown, decades of investment-driven growth, and a trade war with the U.S. that is set to re-accelerate. Faced with these headwinds, policymakers have recommitted to monetary and fiscal stimulus to boost domestic demand. This is critical for durable growth, but how the money is spent is almost as important as how much. To date, the strategies deployed by policymakers harken back to those in post-asset bubble Japan rather than the reforms and spending that have been called for. An extension of the approach employed thus far risks proving inadequate to materially lift China’s soft inflation or help reset the country on a sustainable growth trajectory.

For North American firms and households, the implications are two-fold; (1) the absence of domestic pricing power will likely imply margin compression and reduced profitability for foreign firms operating in China, and (2) the course of the trade war will determine if, and when, the global disinflationary force from China’s excess supply manifests.

The Base Case

We expect China’s growth to clock in at 4.8% in 2024, in line with the 5%-ish target set out by policymakers. Next year, authorities are likely to set a growth target of around 5%, along with an expansion in the fiscal deficit1. However, risks are tilted to the downside and our forecast is for a 4.7% expansion, a virtual repeat of this year’s performance, as the trade war with the U.S. gains steam. There is ample uncertainty around this forecast as the scale and scope of tariffs, along with the size of the policy response from China’s authorities, remains unknown.

Consumer spending has expanded well below its pre-pandemic pace (Chart 1). October’s retail spending figures were a welcome uptick as the latest round of stimulus measures (in part the cash-for-clunkers program for household appliances) helped lift spending, but November saw a give-back of some of the gains. Ample capacity remains, and with home prices continuing to correct (albeit at a slower pace2), consumer confidence is likely to be locked in the doldrums, resulting in a protracted recovery.

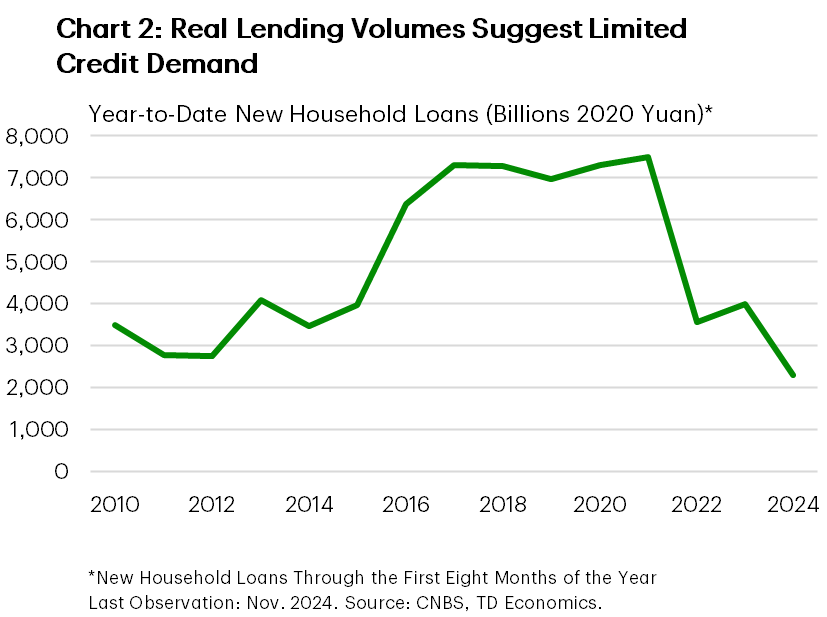

A soft outlook for household demand is the driving force behind our expectation for a near-absence of inflation in 2025. Weakness in indicators of consumers’ assessment of prospects add conviction to this view. Loan demand remains tepid, with new loan growth failing to gain traction in the months after interest rate cuts. This signals a preference towards paying down balances and rebuilding balance sheets (Chart 2). The upshot is that incremental increases in incomes would be diverted to balance sheet repair rather than capacity absorbing net-new demand.

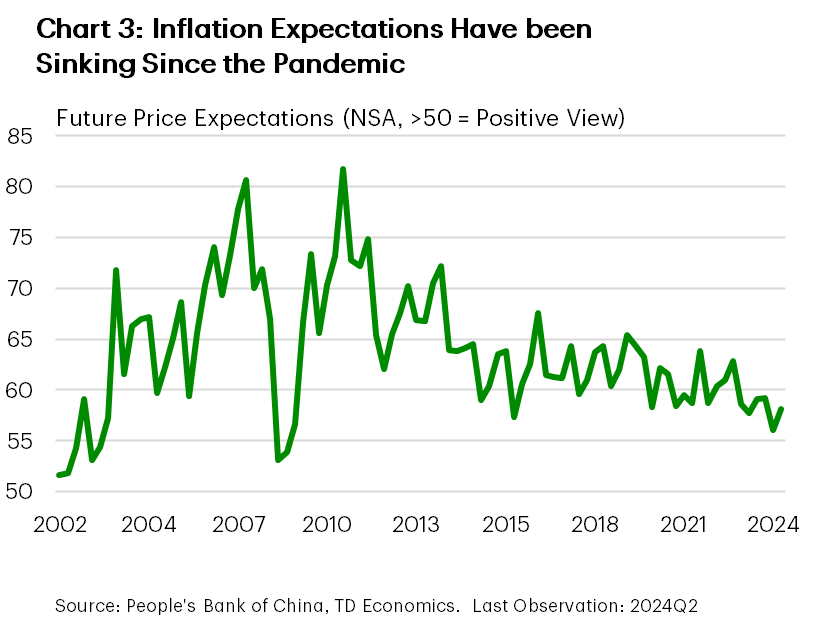

Thus far, price growth has continued to cool with both economy-wide measures (the GDP deflator) and consumer prices in, or near, deflationary territory. The weak pricing environment is bleeding through to inflation expectations, measures of which have been on a downward trajectory for months (Chart 3).

The risk is that this spirals into a deflationary trap, where falling prices create a self-reinforcing loop of delayed demand, increased savings, and further economic weakness. This would add further global disinflationary pressure, while also weighing on foreign firms’ investment returns in China.

The Trade War is About to Flare Up

The trade war between the U.S. and China never went away when the Biden administration took over in 2021. While rhetoric cooled, and U.S. allies were no longer overtly threatened with tariffs, restrictions on China’s access to critical U.S. components were ramped up and tariffs were kept in place.

We have already gotten a hint of how China will respond to additional tariffs. Using a set of new laws and regulations, authorities are now willing and able to target individual firms and limit supplies of key products to other countries. Authorities have used these powers to target companies with ties to the U.S. national security establishment3 and limit the availability of three critical minerals – germanium, gallium and antimony – driving up their prices. Moreover, straightforward tariffs on U.S. agricultural exports are now more feasible than in the past as China has diversified its import sources away from the U.S. in recent years. This allows for retaliatory tariffs while limiting damage to domestic consumers.

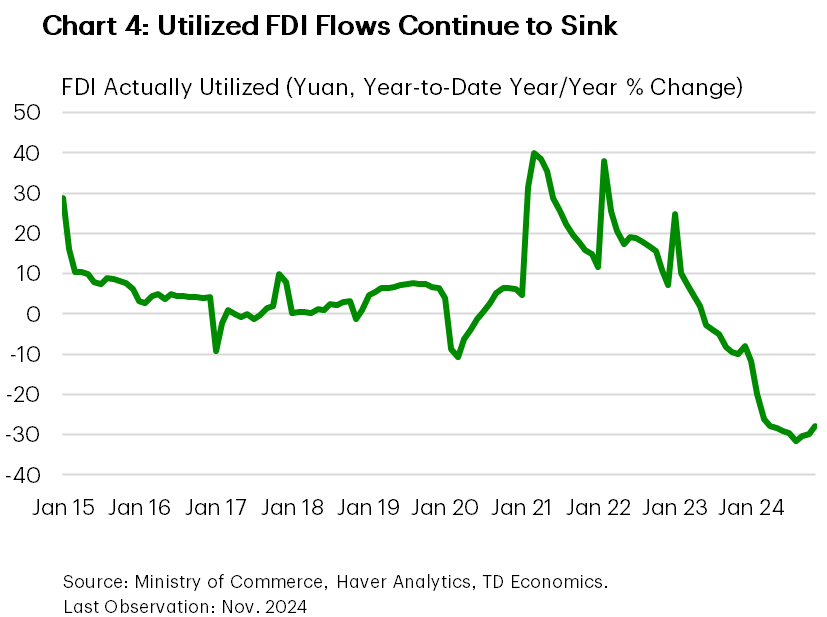

However, these present the worst-case scenario for the trade war. Chinese authorities will likely look to strike a delicate balance between trade retaliation to stand up for their interests and alienating foreign firms through actions perceived as unfriendly to businesses. The tradeoff is important as avoiding disorderly capital flight remains top-of-mind amid a tapering-off of foreign direct investment flows into the country (Chart 4) and the prospect of further yuan devaluation to combat tariff hikes4.

Worrisome Policy Parallels with Japan’s Fiscal Strategy from the 1990s

More fiscal and monetary stimulus is on the way5, but how it is implemented matters greatly for the economy. For this reason, Japan’s experience after the bursting of the asset bubble in the late 1980s is an interesting case study. The focus below is on the ineffectiveness of Japan’s fiscal policy, even though a multitude of factors weighed on growth over the following decade (including a liquidity trap, a credit crunch, and the Asian Financial crisis6).

First, and foremost, Japan’s policymakers remained committed to fiscal discipline7 at a time that growth slowed rapidly. Initial budgets were often not expansionary – and sometimes outright contractionary – only further loosening when the hoped-for growth failed to materialize8. This stop-start dynamic was found to increase uncertainty, undermining the hoped-for growth lift9. This bears an eerie similarity to China’s recent strategy of targeting a 3% deficit, and then making up ground later in the year by allowing it to increase (as in 2023), or through the ad-hoc issuance of special purpose bonds10.

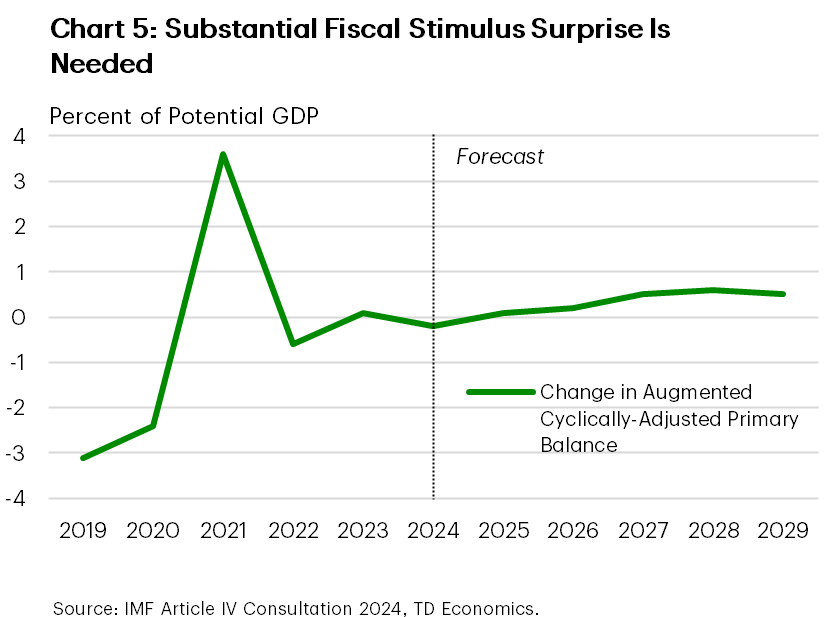

Importantly, this incremental strategy looks set to extend into next year. The IMF’s projection for the Augmented Cyclically Adjusted Primary Balance (a measure of the deficit that includes borrowing from local government funds and strips out the effects of automatic stabilizers) showed that a remarkable degree of restraint was expected around mid-year when the Article IV consultation was done (Chart 5). Even with the new announcements at the Central Economic Work Conference, the official deficit target for 2025 is rumored to be roughly 4%, only moderately higher than the 3% target this year11. It was only later in the month that rumors of a 3 trillion yuan (2.4% of 2023 GDP) special bond issuance to fund consumption support, infrastructure, and bank recapitalization emerged12.

Secondly, Japan relied on local governments to deliver public investment projects, but cash-strapped and highly indebted localities chronically underspent, opting to not to invest in low-return public projects to deliver central government spending promises13. This mirrors the current situation in China where local level governments are operating under large debt burdens with limited revenues. Faced with fewer projects that can meet investment criteria14, and wary to add more debt amid falling land sales, they have not been fully using up their budgeted allotment of special purpose bonds.

The problem is that public investment forms an important avenue for the kind of “Real Water” measures that lift GDP. So, despite years of investment-driven growth eroding the marginal returns on new initiatives15,16, it still forms an important part of the policy prescription. For China, an opportunity exists to use the funds to facilitate the transition to a consumer-driven economy through investments to expand the social safety net.

Lastly, Japan’s announced stimulus was often not allocated to GDP boosting ventures (“Real Water” initiatives). Asset reshuffles to restore balance sheets were often lumped in with headline stimulus figures that, while serving a purpose, were not effective in creating net-new domestic demand and absorbing excess capacity. China faces a similar situation. For instance, the 10 trillion-yuan ($1.4 trillion) announcement for local government debt swaps is an important (and expensive) measure to bring relief to local level balance sheets17, and likely a necessary condition to get increased compliance with the aforementioned additional borrowing, but not stimulating net-new demand on its own.

The Good News

Policymakers continue to say all the right things. Monetary policy is going to be “moderately loose”, and authorities stressed the importance of spurring consumer demand at December’s Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC)18. An expansion of the evidently effective cash-for-clunkers program for consumer goods is in the cards. Rumors of a large special bond issuance (2.4% of 2023 GDP) to bankroll the scheme and fund strategic investments have also emerged in the past weeks19. Optimistically, reporting from the CEWC, contained language on solidifying the social safety net20. The effective expansion of social supports would help create room for the persistently high household savings rate to fall, a necessary condition for the sustainable rotation to a consumption led growth model.

All the focus on the consumer will be needed as the effectiveness of additional monetary stimulus is highly uncertain. Sinking credit demand suggests that looser monetary policy may have a small impact on growth as, even at lower rates, borrowers don’t see much upside to increasing leverage. That said, supporting asset prices to prevent a steep correction21 (likely in the hopes of propping up consumer sentiment and stimulating a wealth effect) is part of the stimulus playbook.

To avoid a credit crunch, capital buffers at major banks were proactively increased in September22, helping absorb some of the ongoing margin compression from a cut to existing mortgage rates and lower long-term rates. As major banks are relied upon to implement credit expansions23, preemptively shoring up balance sheets should help ease the burden of lending in a more challenging environment.

Lastly, at its Third Plenum in the summer, authorities began reforms to add more revenue levers for local governments. In particular, the gradual move to “pass collection power to local government”24 of excise taxes is an important transition to provide local government an alternative to land sales as a revenue source.

Bottom Line

At the CEWC, authorities said all the right things, pledging to deploy fiscal and monetary stimulus to boost domestic demand and create the conditions to develop a consumer driven economy. That’s all well and good, but now we need to see it in practice. The rumored expansion of the deficit to 4%, along with a 5% growth target for 2025 suggest that the piecemeal approach to policy will continue, with comprehensive reforms to bolster the social safety net and wean off the investment driven growth model being kicked further down the road.

Absent a coordinated fiscal and monetary impulse, domestic demand is likely to be insufficient to absorb the economy’s productive capacity. This means ongoing downward pressure on prices. This also implies exports will continue to be a key source of real growth, raising the risk of drawing the ire of trade partners that could be inundated with relatively inexpensive products. A tail risk is that severe trade retaliation from the U.S. and others results in a whipsaw effect on prices as tit-for-tat escalations results in China implementing severe export restrictions on critical components.

For the global outlook the implications are twofold. First, with or without new U.S. tariffs, the absence of a large stimulus effort means demand for commodity inputs is unlikely to surge. For global consumers of commodities, this provides an element of stability to the price outlook and thus global producer prices. Moreover, a steep devaluation of the yuan could make Chinese exports relatively cheaper, adding another disinflationary force on input prices.

Secondly, for North American firms with substantial investments in China, the downbeat domestic situation could weigh on sales activity and investment returns. For some perspective, Canadian multinational enterprises reported sales equivalent to almost 0.7% of GDP in China in 2023. U.S. data are slightly more lagged, but majority owned affiliates reported sales equivalent to 1.9% of GDP in 2022. Moreover, with trade tensions escalating, uncertainty about the prospective returns on hundreds of billions of dollars of assets in China increases.

So, now we wait. A concerted and coordinated approach to stimulus could lift China’s prospects for 2025 and beyond, facilitating the rotation to a consumer driven economy. Much like in the U.S., the decisions by key policymakers in the coming months could have widespread ramifications.